Netgear DM 200 Modem Breakdown - The Software Side

Motivated by miscellany blog posts, I decided to try my hand at poking around an old modem I had lying around.

This is a part of my series on taking apart the netgear DM 200 modem

For more posts on this, see below

- Netgear DM 200 Modem Breakdown - The Software Side (You are Here)

- Netgear DM 200 Modem Breakdown - The Hardware Side

It’s a netgear DM200, ADSL/VDSL modem/router (I will be calling it either a router or modem in this blog post, depending on my mood). My plan is first do some recon and poking the software, without opening up or doing any hardware shenanigans. Once I have a grip on what’s happening, I’ll then open it up and see if I can do some lower-level reverse engineering. So let’s get started!

Exploring Firmware

I pulled the current version of the firmware from their website: https://www.netgear.com/support/product/DM200.aspx#download. The firmware is actually a complete copy of the software running on the modem, so I can play with that and get a somewhat accurate look at what’s currently running on my modem. Since I haven’t updated the firmware on the physical modem I have, the version I downloaded online may be a newer version than what is currently on it, but it can give me some initial info and hypothesis I can use later.

Since I had recently played around with the Swag Bag Lab from wild west hackin’ fest ( https://wildwesthackinfest.com/deadwood/sbl-instructions), I knew binwalk was a reverse engineering tool you could use in linux, so I started with that.

After I downloaded the image, I used the below command to find out more about the .img file I got.

~/Downloads/DM200_V1.0.0.66$ binwalk --signature --term ./DM200-V1.0.0.66.img

Explanation –signature flag is for finding signature of file types in img, –term to resize to fit the terminal window. Binwalk goes through the file and looks for special signatures that denote a particular file type. Blog post here describes it: https://embeddedbits.org/reverse-engineering-router-firmware-with-binwalk

The binwalk command gave me this (apologies for the bad formatting):

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

128 0x80 uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0x5BEA65A6, created: 2020-08-11 07:24:23, image size:

1625568 bytes, Data Address: 0x80002000, Entry Point: 0x8000A970, data CRC: 0x8FE0035E, OS: Linux, CPU:

MIPS, image type: OS Kernel Image, compression type: lzma, image name: "MIPS LTQCPE Linux-3.10.12"

192 0xC0 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 8388608 bytes, uncompressed size: 4872776 bytes

1638464 0x190040 uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0x4458CD93, created: 2020-08-11 07:24:32, image size:

475136 bytes, Data Address: 0x40908000, Entry Point: 0x40908000, data CRC: 0xE383D3B5, OS: Linux, CPU:

MIPS, image type: OS Kernel Image, compression type: lzma, image name: "Linux-3.10.12"

1638528 0x190080 Squashfs filesystem, little endian, version 4.0, compression:xz, size: 474431 bytes, 3 inodes,

blocksize: 131072 bytes, created: 2020-08-11 07:24:31

2162752 0x210040 uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0xA33A8813, created: 2020-08-11 07:24:32, image size:

5148672 bytes, Data Address: 0x40908000, Entry Point: 0x40908000, data CRC: 0xAAF2E52, OS: Linux, CPU:

MIPS, image type: OS Kernel Image, compression type: lzma, image name: "Linux-3.10.12"

2162816 0x210080 Squashfs filesystem, little endian, version 4.0, compression:xz, size: 5147702 bytes, 2308 inodes,

blocksize: 131072 bytes, created: 2020-08-11 07:24:30

So I can see it uses a MIPS Linux, presumably the version listed as “Linux-3.10.12”. I hadn’t heard of MIPS linux before so I had to do some research. MIPS is an instruction set, and MIPS Linux is a Linux distro that is compiled for MIPS. So similar to ARM architecture, but MIPS is used more for routers and gateways. Funnily enough, according to wikipedia, the N64, Playstation 1 and 2, and the PSP all used MIPS!

It also uses squashfs, which wikipedia says: is a compressed read-only file system for Linux. Squashfs can be uncompressed with binwalk, and I can then poke around at the filesystem of the MIPS linux without actually running any linux kernels or hacking into the modem’s system or anything.

~/Downloads/DM200_V1.0.0.66$ binwalk -Me DM200_V1.0.0.66.img

Explanation: -e means extract the files found by binwalk (including extracting the squashfs), -M means do it recursively (stands for Matroyshka, a la matryoshka dolls, I assume)

Once binwalk finishes, I can continue my poking! I didn’t have tons of ideas of what to look for specifically, so I was using various blog posts to spark ideas. One was looking for a /etc/banner to find out more about the linux distro (which they do here: https://embeddedbits.org/reverse-engineering-router-firmware-with-binwalk/)

~/Downloads/DM200_V1.0.0.66$ cd _DM200-V1.0.0.66.img.extracted/

~/Downloads/DM200_V1.0.0.66/_DM200-V1.0.0.66.img.extracted$ cd squashfs-root0

~/Downloads/DM200_V1.0.0.66/_DM200-V1.0.0.66.img.extracted/squashfs-root-0$ cat ./etc/banner

+---------------------------------------------+

| Lantiq UGW Software UGW-6.1.1 on XRX200 CPE |

+---------------------------------------------+

Well that seems like a bunch of gibberish. DuckDuckGo to the rescue! Looks like Lantiq was a semiconductor company bought out by Intel in 2015. They manufactured SoC (system on chip) for home networking. So I bet then if I open up this modem it’ll have a Lantiq chip inside. That’s cool, I can tell just by looking at some software!

Just searching for the string “Lantiq UGW Software UGW-6.1.1 on XRX200 CPE” led me to the website openwrt: https://openwrt.org/toh/netgear/dm200. They have lots of info about this particular router. OpenWrt is a linux operating system targeting embedded devices. The page I got is explaining how to replace the default firmware that Netgear puts in it with the OpenWrt software. It also has a hardware section that shows me a serial pinout and the order of the pins. Sweet! So when I open it up, I can try to connect my bus pirate or ch341a to try to get access to the modem’s code directly! At least I think I can use either of those for this purpose. I haven’t done it before, so I guess I’ll find out later.

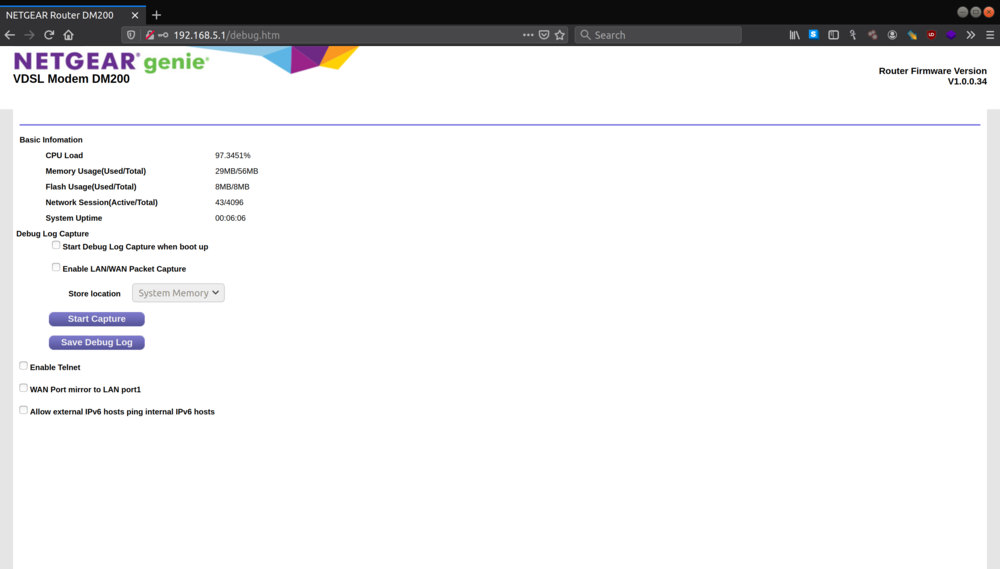

Another useful section is the Misc section, where it mentions there’s an advanced debug page accessible in the router’s website at http://192.168.5.1/debug.htm. Most routers and modems normally host their own websites that end users can log into to modify various router settings (wifi, passwords, etc.). Now I know the IP that the website will probably be hosted on when I plug it in. And apparently the debug page lets you toggle on telnet access to the router. So I won’t even have to open it up to start mucking with the OS running on my modem.

However, I don’t want to take random internet sites at face value, so I decide to double check the firmware to see if there is such a debug.htm file. I noticed in the firmware’s file system there’s a www folder. That’s a common folder to host a website at, and when I open it up, sure enough, there’s a bunch of htm files. So a quick look for a debug.htm…

~/Downloads/DM200_V1.0.0.66/_DM200-V1.0.0.66.img.extracted/squashfs-root-0/www$ ls | grep debug

collect_debug.txt

debug.cgi

debug_cloud.cgi

debug_detail.htm

debug.htm

debuginfo.htm

debug_run.htm

NTP_debug.htm

Bam jackpot, debug.htm. Plus a bunch of other files I may want to take a look at. Almost time to plug in my modem!

But first I had a question. A lot of the router reverse engineer blog posts I saw mentioned busybox, a software suite that provides several Unix utilities in a single executable file. But so far I haven’t seen anything that says busybox on it. Executables are stored in /bin, so I took a peek to see what sort of executables this filesystem has:

~/Downloads/DM200_V1.0.0.66/_DM200-V1.0.0.66.img.extracted/squashfs-root-0$ ls bin

adduser chgrp datalib dmesg getopt ipcalc.sh mkdir nice ps rmdir sync uname

ash chmod date dnsdomainname grep kill mknod nvram pwd sed tar usleep

busybox chown dd echo gunzip ln mount pidof readycloud_nvram sh touch vi

busybox2 config deluser egrep gzip login mv ping rev sleep true zcat

cat cp df fgrep hostname ls netstat ping6 rm su umount

Ah, there’s busybox! There’s also two executables that still have .sh after them, representing shell scripts. Those look custom, maybe just for this modem? Reading through them, the ipcalc literally seems a way to figure out the ip start and end range and other IP calculation work. Which makes sense for a router. I’m unsure what the login.sh is for. Though I do see at the start there’s a comment:

# Copyright (C) 2006-2011 OpenWrt.org

Hey, that’s the website from earlier! So maybe Netgear or Lantiq started with a copy of OpenWrt and then modified it for their modem? More questions to try to answer!

There’s a lot of other searching I can do, but for now, I think the next best step is to actually connect to the modem, and see if I can get telnet up like OpenWrt mentions.

Connecting to the Modem

The router I had lying around included the box and default cables, so I could use the included ethernet cable to connect to my laptop, and the power cord to turn it on, and I was off to the races.

First step was to hit the URL I found earlier and try to turn on telnet

It requires me to give it a username and password, but looking at the manual online https://www.downloads.netgear.com/files/GDC/DM200/DM200_UM_EN.pdf, I can see that the username and password is most likely admin/password. Type that, and I’m in! There’s the handy “enable telnet” button. Once that’s turned on, I connect from my laptop using telnet and voila, I’m dropped into a shell, no password required!

BusyBox v1.17.1 (2016-04-29 07:02:59 EDT) built-in shell (ash)

Enter 'help' for a list of built-in commands.

/ # help

Built-in commands:

------------------

. : [ [[ alias bg break cd chdir command continue eval exec exit

export false fg hash help jobs kill let local printf pwd read

readonly return set shift source test times trap true type ulimit

umask unalias unset wait

Cool, so there’s some built-in commands, and it says right at the top it’s running BusyBox from 2016. That makes sense, this router/modem was released in 2016.

I did try some standard bash commands (ls, cat) and they seem to work though, so it looks like that help isn’t quite accurate. I looked in the /bin folder, and it looks like all the standard bash commands are there. So I can still use all my linux bash-fu to poke around in the software.

Because a lot of the blogs I found focused on finding vulnerabilities in the firmware, they all suggest hunting for things like passwords in plain text. I ran some grep commands hunting for passwords, but didn’t find anything good. I tried some other greps and nothing else really popped. So I moved on to exploring /etc and /var. The /etc folder normally has lots of configuration files and the like, so it can be an interesting place to explore. The /var folder stores logs, and it can reveal info like the sort of processes being run.

Running through the etc folder I came across some interesting configuration files. Here’s a quick rundown of some of the files

OpenWrt

I found a couple files, openwrt_version and openwrt_release, which confirms this modem/router is running a customized copy of OpenWrt. Interestingly enough, OpenWRT 12.09 came out in 2013 in April, even though this modem came out in 2016. So on release it was already running a 3 year old version of OpenWrt. I’ve heard that a lot of modems and routers are like this, where offcial copies of firmware are often running on out of date (and therefore often insecure) software, but it’s good to see confirmation myself!

/etc # cat openwrt_version

12.09

/etc # cat openwrt_release

DISTRIB_ID="OpenWrt"

DISTRIB_RELEASE="Attitude Adjustment"

DISTRIB_REVISION="12.09_ltq"

DISTRIB_CODENAME="attitude_adjustment"

DISTRIB_TARGET="lantiq/xrx200"

DISTRIB_DESCRIPTION="OpenWrt Attitude Adjustment 12.09"

Device Info

Opening up /etc/sys.conf, I could see for myself some more confirmation it was manufactured by Lantiq Communications. The lantiq.com link now goes to the home page of intel, since they were bought out. Also, it’s kind of funny, this modem was released in 2016 and says it was made by Lantiq, but Lantiq was already bought out by Intel by that point (since it was bought in 2015). So this router must have been released in that weird in-between time after a company is bought out by another.

/etc # cat sys.conf

#<< device_info

device_info_manu="Lantiq Communications"

device_info_oui="AC9A96"

device_info_modname="UT300R2U"

device_info_friendlyname="xDSLRouter"

device_info_prodclass="CPE"

device_info_sernum="DMA66"

device_info_specver="1.0"

device_info_modnum="1.0"

device_info_tr64url="http://www.lantiq.com"

#>> device_info

“Encoded” Passwords

One of the files I found looks to contain configuration info for the DSL connection back to the ISP. There it was the old username of the person who owned this modem last (my parents), as well as their password for the ISP, that was “encoded” using base64. The conn_type of “pppoe” I’m assuming is setting the connection type from my modem to the ISP, and is referencing “Point-to-Point Protocol over Ethernet”. Wikipedia explains this protocol is the solution for tunneling packets over the DSL connection to the ISP’s IP network, and from there to the rest of the Internet. I’m guessing this is the username and password that they would also use to sign in to the ISP’s website to pay their bill and update their internet connection. This seems like a bad set up to me, since base64 isn’t really an encryption, and the big rule for passwords is always hash and salt them, but hey, I’m not a huge corporation that was bought by Intel, so what do I know?

/etc # cat lantiq_dsl_wan.conf

cfg_wan_mode="adsl_atm"

cfg_conn_type="pppoe"

cfg_vlan=""

cfg_pri=""

cfg_vpi="0"

cfg_vci="35"

cfg_encaps="llc"

cfg_qos=""

cfg_username="DSL USERNAME"

cfg_password="PASSWORD IN BASE64"

No Hacker Protection, sadly

One configuration file that just had TONS of info in it was the rc.conf file. I browsed through it quickly, since I mostly didn’t know what I was looking for, but did find some interesting sections. My personal favorite is this:

ENABLE_HACKER_ATTACK_PROTECT="0"

Presumably “0” is false, so this modem/router is not protected from hackers. All well, more fun for me!

System Password in plain text?

Another section that looks worrying is this:

#<< system_password ##56

Password="admin"

PasswdProtect="0"

#>> system_password

The Protect variable is presumably set to false, so the fact this password is clearly in plain text isn’t an issue for now, but that seems bad. Also, I’m not sure what system password this is referring to, so far the only password I had to type in was “password”, which netgear tells me about. Maybe it’s for if I want to add a password to root later?

FTP users?

Still in rc.conf, I find below. That looks an awful lot like something you’d see in a /etc/passwd or /etc/shadow. When I had read the OpenWrt page on this, the misc. Section talked about a plain text FTP username and password. There’s a script that uploads log files to a specific IP address, and it has hardcoded, plain text username and password. I’m guessing that’s the same user as this one. Also…not great. I didn’t check out the IP or try the username or password because that seems stupid to do, but according to OpenWrt, malware has been uploaded in all places people can reach, which seems consistent with the internet.

#<< password_file ##120

passFileLineCount='1'

passFileLineCount0='ftp:[mysterious gibberish, possibly hashed password]:100:100:ftp:/tmp:/dev/null'

#>> password_file

Remember when Yahoo was big?

I have no idea what this section does, but I’m entertained there’s some hardcoded Yahoo variables. Why does a modem need to know about YAHOO_STATUS and ports?

#<< dos_applications ##280

HOTSYNC_STATUS="0"

HOTSYNC_PORT="14238"

OLD_HOTSYNC_PORT="14238"

YAHOO_STATUS="0"

YAHOO_PORT="5010"

OLD_YAHOO_PORT="5010"

MIME_STATUS="0"

MIME_PORT="25"

OLD_MIME_PORT="25"

CODERED2_STATUS="0"

CODERED_STATUS="0"

ICQ_STATUS="0"

WEB_PORT="80"

OLD_WEB_PORT="80"

#>> dos_applications

Conclusion

Well that’s all the poking around I’ve done so far, and the interesting things I’ve found. Next up, opening up the modem and trying to identify some hardware and what it does. Plus, trying to connect to it using the serial connection ports like a hardware dev, and trying not to fry anything too important!

References

Want to see more firmware and modem/router reversing? Here’s a list of the blog posts I found useful:

https://jcjc-dev.com/2016/04/08/reversing-huawei-router-1-find-uart Focused on the physical hardware side more than exploring the firmware, but super helpful for learning about the basics of poking at hardware!

https://simonfredsted.com/996 Focused more on firmware side of things

https://embeddedbits.org/reverse-engineering-router-firmware-with-binwalk Also firmware, talks a lot about binwalk and its uses